Origin

Where do you come from?

Ethnic origin refers to a person’s roots. External features can be, among others, skin colour, linguistic peculiarities or affiliation to a particular ethnic group.

If a person looks different to the majority, that person is quickly perceived as alien or foreign and asked, “Where do you come from?” The question may seem innocuous, but the person asked often gets annoyed because the question also means, “You’re not from here”.

People perceived as alien or foreign often experience discrimination, be it when looking for accommodation, applying for a job or during police checks. Often these are people with an immigrant background or indigenous population groups in colonialized countries. The more striking the difference, be it due to skin colour or a religious symbols like a headscarf or a kippa, the stronger the reactions. And how those affected perceive themselves and whether they are locals or foreigners, refugees or migrants, is irrelevant.

Strangers in one’s own country? Everyday racism in Germany / DW German

Apartheid

In South Africa, the original population was suppressed and enslaved from the moment colonialization took place. The white Boers, descendants of the Dutch, and later the English regarded themselves as superior to the Blacks.

Apartheid was introduced officially when the National Party came to power in 1948. From then on, people were separated rigorously according to their skin colour. All those categorised as not white were discriminated against, politically, economically and socially. That means, for example, that they were not permitted to vote, were resettled and prohibited from leaving certain areas. They also had to carry special passports. Laws stipulated that white and non-white persons were not allowed to love one another or get married. That unjust regime did not come to an end until 1994, when the African National Congress, ANC, came to power and Nelson Mandela (1918–2013) became president.

«I’m reclaiming my Blackness»

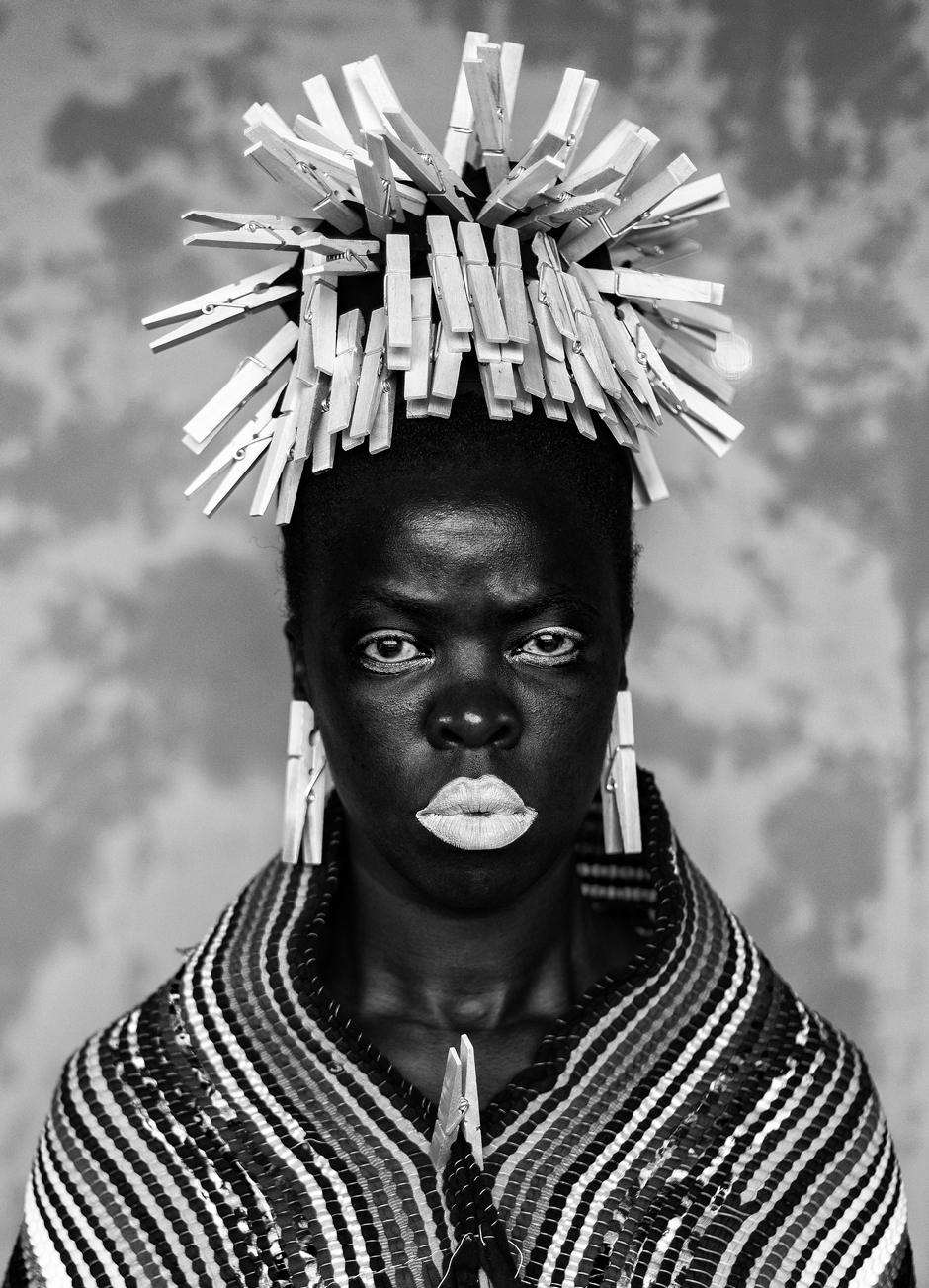

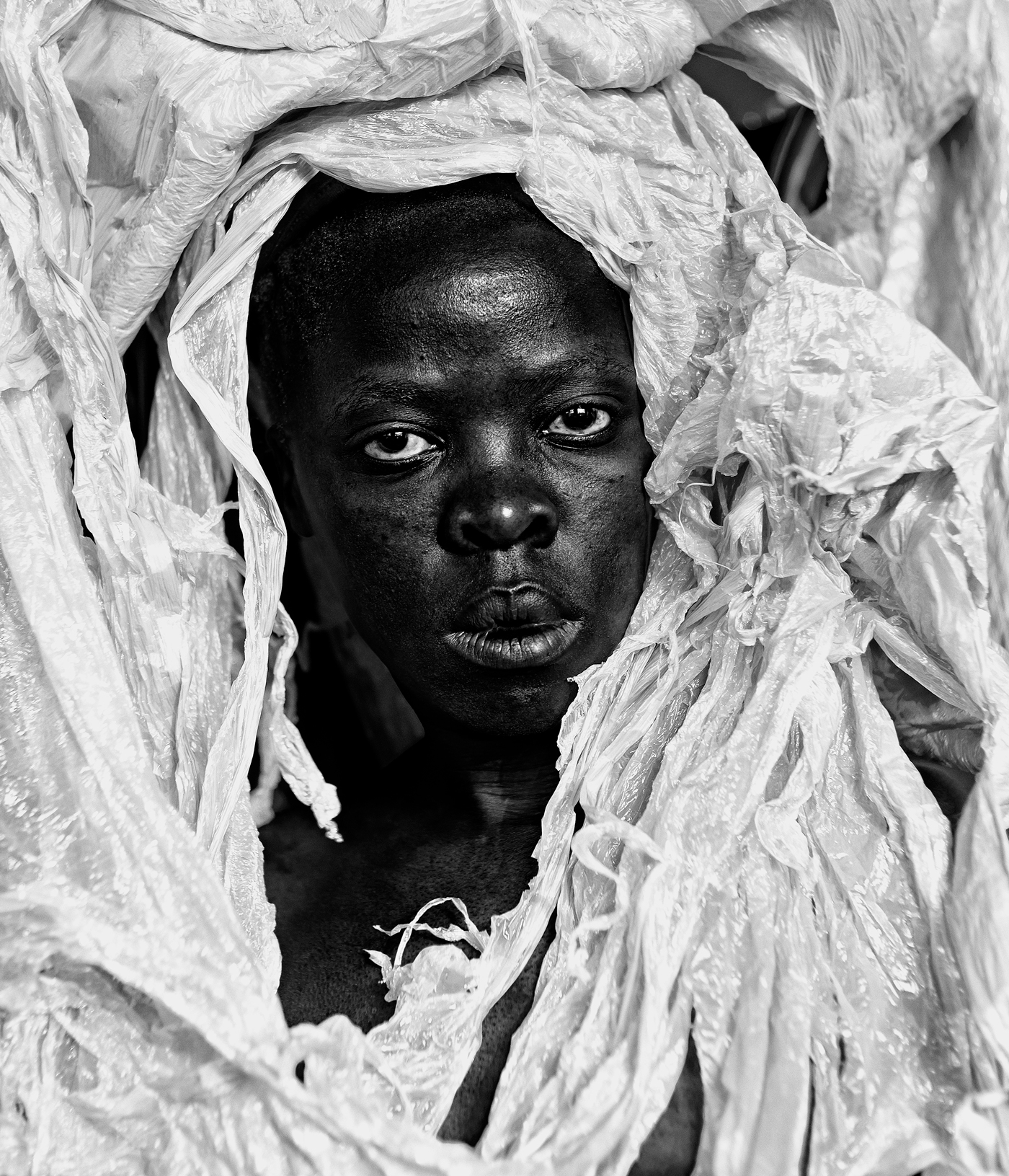

In their self-portraits, Zanele Muholi incorporates stereotypes, which illustrate how Black women have been depicted over the course of history. Some of the images address the theme of systemic violence, others question repressive stereotypes like those that appear in ethnographic depictions, for examples. The title of the work series Somnyama Ngonyama means “Hail the Dark Lioness” in English.

By using banal household items for their settings, Muholi points to the socio-cultural restrictions to which Black women are subject. Muholi heightens the contrast in these self-portraits by exaggerating the darkness of the skin. In this context Muholi says, “I’m reclaiming my Blackness, which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged other.”

Qiniso, The Sails, Durban, 2019

Qiniso means “truth” in isiZulu. Muholi’s hair is adorned with Afro combs, an accessory specially developed for the hair of Black people. On the African continent and in the African diaspora, the respective hairstyles symbolize counter-culture, resistance and pride. The Afro comb has been a status symbol in many African societies for centuries.

Bester I, Mayotte, 2015

The Bester-portraits pay homage to Muholi’s mother, who worked for more than forty years as a domestic servant for a white family. She supported her family of eight alone. During Apartheid, laws such as the Job Reservation Act People of Colour forced people like her to take poorly paid jobs or work as “unskilled labour”. With their Bester self-portraits Muholi acknowledges the many domestic servants whose contribution to the wealth of their families is not often recognised. The materials used here, and which point to Bester’s work in the household, are arranged like a crown.

Racial Profiling

“Racial Profiling” means that people who are perceived as being different are classified as “dangerous” and for this reason are checked more frequently by the police. This kind of discrimination often happens to Black people.

This picture shows Muholi behind a sheet of plastic otherwise used to protect luggage on a journey. It addresses the theme of racial profiling and the constant checks to which Black people are subjected when they cross a border. The picture also speaks of the need for protection and the feeling of being exposed and robbed of one’s dignity. The title means “enough”.

Zanele Muholi says, «Black people are asked questions which people of other origins are not asked: What are you doing here? When are you going back? When this happens, they feel like scum.

The pencil test

This self-portrait refers to the “pencil test”. This was a racist practice required by the South African government during Apartheid. If officials were unsure whether a person should be classified as white or not, they stuck a pencil into their hair. If the pencil fell out, the hair was considered to be straight and not frizzy. The person thus “passed” the test and was classified as white. The picture criticises tests and theories that legitimize discrimination. The title means “passed”.